Who are the Sateré-Mawé ?

According to an article from the Povo Indigenas No Brasil when translated from Portuguese to English means, Indigenous people in Brazil; the English translated meaning of the name Sateré-Mawé people is derived in the first part as the name of the ruling clan (Sateré meaning “burning caterpillar”) and in the second part (Mawé meaning “intelligent and curious parrot”).[1]

The language has a unique story of its origin and linguistic family, Povo Indigenas No Brasil describes the language as:

The Sateré-Mawé language is part of the Tupi linguistic branch. According to ethnographer Curt Nimuendaju (1948), it differs from the Guarani-Tupinambá. Pronouns are the same as those of the Curuaya-Munduruku language, and the grammar is, it seems, Tupi. But the Mawé vocabulary contains elements that are entirely different from Tupi and cannot be related to any other linguistic family. Since the 18th Century their repertoire includes many words from the Língua Geral (the language spoken in colonial Brazil until the late 18th Century, a mixture of Indians languages and Portuguese).

Today most Sateré-Mawé men are bilingual – they speak their own language and Portuguese; women, on the other hand, tend to speak only Sateré-Mawé, despite this people’s three centuries of exposure to the national society.[2]

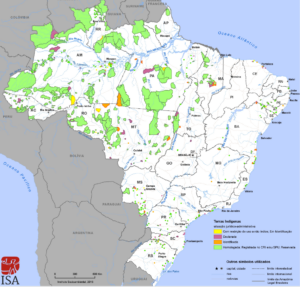

The Sateré-Mawé live in the region of the mid Amazon River, on the border of the Brazilian states of Amazonas and Pará. With a total area of 788,528 hectares which equates to 1,948,495.1224 acres.[3] This is a land size of 3,044.524 square miles. Slightly, bigger than the state of Delaware’s 2,489 square miles.[4]

Imagine how many distinct language variances could exist in the American state of Delaware alone – It is then not hard to imagine the possible myriads of variances which could present themselves within an entire distinct people group with their own unique language. It would reason that translating any written word let alone the Word of God is a monumental undertaking.

Comment by John Wilkinson: Although there are differences in vocabulary between the Sateré people, who live on 7-8 different rivers, there are insufficient differences to qualify for a separate dialect which would require around 50% difference.

The people from the different rivers often travel to other rivers and I can personally vouch for the fact that the people can totally understand each other having travelled to other rivers myself and finding that I am also able to understand folk from the Marau, Urupadi and Miriti rivers.

However, although the differences don’t warrant a separate Bible translation (IMO), this in no way diminishes the difficulties of the task of Bible translators which is totally God’s work, and our work is to totally depend upon Him moment by moment as He uses us to translate His word.

Indigenous Lands – Brazil

Sateré-Mawé Language

Missionary to the Sateré-Mawé and Bible translator John Wilkinson shares with Missions Geographic Magazine that there isn’t a specific word for “HELLO” in the Sateré language.

Generally speaking, when people greet each other, they may use a variety of terms such as good morning – ihot’ok, good afternoon – he’ika’at, or good evening – wãtym. But a common greeting when people say “hi” is a word which really is used to ask how the person is doing, i.e. waku – which literally translated means good. But when used in the context of a greeting it can mean “how’s it going,” “how are you doing,” ” Is everything good?”